Many moons ago powdered wigs were all the rage — a fashion seemingly started by The Sun King, aka Louis XIV, who noticed he was going bald at the tender age of 17 and no doubt felt this might limit his sex appeal. Mind you, as syphilis is thought to have caused his hair failure, you might think that quite enough of a turn-off — though maybe not in the jolly old Court of Versailles.

Whatever, when Charles II followed the trend in England, it was wigs for all.

Shifting an itch

In fact there was some science behind the fad in that, back in the 17th century, head lice (nits as we might say) were a problem. When heads were shaved and wigs fitted the nits simply moved upstairs and could be dealt with on laundry day.

What’s new?

Wigs have come and gone but man’s hair anxiety remains — as judged by the number of hairy potions you can buy on line and the fact that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved two drugs to treat male pattern baldness (i.e. a receding front hair line or a bald spot). You can even buy a baseball cap with built-in hair re-growth promoting lasers for £1200.

There’s nothing odd about hair loss — it happens all the time to the tune of up to 100 hairs a day — and pattern hair loss is also common, appearing (disappearing might be a better word) in about 50% of men and a quarter of women by age 50 — generally put down to genetics, age and male hormones. The technical term for hair thinning or balding is hair follicle miniaturization — meaning that the follicles, originally producers of healthy hairs, start making thinner hairs with a fragile shaft that can easily fall out. Thus hair loss arises from damage to or depletion of hair follicle stem cells (HFSCs).

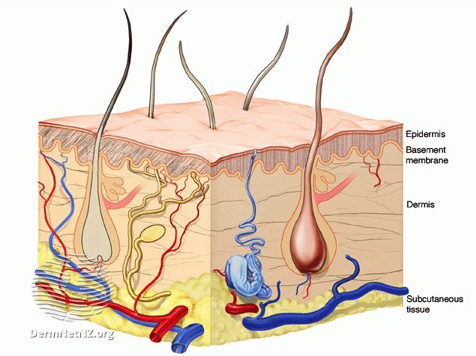

Structure of normal skin. DermNet NZ.

So it’s an age-old problem — but now there’s a new player in the shape of obesity and the cumulative evidence that, by heightening the risk of a range of conditions (from diabetes to heart disease and cancers), excess weight can also lead to hair loss.

Even so, a direct link between the global epidemic of obesity and baldness has been lacking. Step forward Hironobu Morinaga, Emi Nishimura and colleagues from the University of Tokyo with some very convincing experiments that involved feeding mice a high-fat diet (HFD).

Tubby and bald

Spoiler alert! as they say these days: the HFD made the mice gain weight: obesity-induced stress then led to hair thinning. This is clearly visible in the photos below and the degree of hair loss did indeed correlate with increased body weight in HFD-fed mice. Note that this effect is entirely down to diet. Mouse fans may know that they (mice, that is — though we have it too) have a gene (TUB) that makes the tubby protein — and mice with a mutated tubby become obese and deaf, the latter because they lose hair cells.

Obesity accelerates hair loss in mice. Top: Mice fed for six months on a normal diet. Bottom: Mice fed for six months on a high fat diet. Note the bald patch. Morinaga et al. 2021.

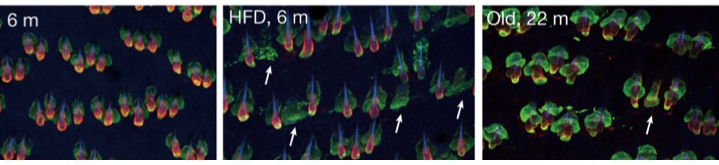

Almost more dramatic than the mice going bald were the efforts of the group to track down what was happening at the cell and molecular level. The HFD caused epidermal keratinization of HFSCs although it did not reduce their number. This means that in the outmost layer of skin the cell content (cytoplasm) is replaced by the fibrous protein keratin and the cells begin to die. It is clear from the images below that the HFD causes loss of normal cells (tagged red) and, after six months, the hair follicle cells are tending to resemble those in aged mice that are predominantly green (i.e. keratinized).

Obesity causes loss of hair follicle stem cells. Left: Mice fed for six months on a normal diet; Centre: High fat diet; Right: Old mice (22 months). Red marker: a protein (COL17A1) that regulates HFSC self-renewal and ageing; Green marker: Keratin 14, a marker for keratinocytes, the primary cell type of the epidermis. Arrows indicate follicles without a detectable HFSC-containing bulge. Morinaga et al. 2021.

They were also able to show that keeping mice on the HFD caused fat droplets to accumulate in HFSCs — much as was recently shown for immune cells (see Fatbergs Block Cancer Defences), a way by which obesity paralyses the immune response to tumours.

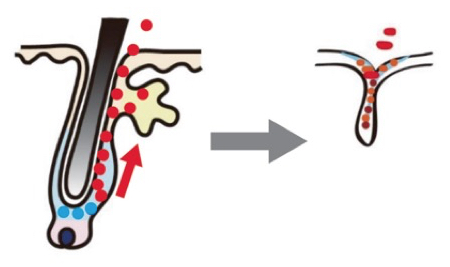

Mechanism of hair loss. Loss of hair follicle stem cells (blue dots) and increase in keratinized cells (red dots) leading to hair thinning/hair loss. Morinaga et al. 2021.

The upshot of fat build up in HFSCs is the blockade of a signalling pathway (called Sonic Hedgehog, controlled by a protein (SHH) that regulates embryonic development, not a turbocharged blue hedgehog). This block leads to elimination of fat-laden HFSCs — hair loss.

Keeping your hair on

All of this means that inflammatory signals that occur in obesity caused by a Western diet — i.e. a high fat diet including red meat, processed meat, pre-packaged foods, high-fat dairy products, etc. — can repress organ regeneration signals, one result being hair follicle miniaturization and baldness. For those with hair concerns we should note that activation of SHH in transgenic mice rescued HFD-induced hair loss and the same effect was produced by a drug that turns on the Sonic Hedgehog pathway Not an invitation to start gorging on burgers without worrying about going bald but an indication that we may ultimately be able to control these complex signalling pathways!

Reference

Morinaga, H., Mohri, Y., Grachtchouk, M. et al. (2021). Obesity accelerates hair thinning by stem cell-centric converging mechanisms. Nature 595, 266–271.