I’ve been ever so lucky in spending a lifetime in science — particularly in cancer biology because, even in the 21st century, every couple of weeks or so you spot some piece of work that makes your jaw drop as you mumble “Wow! That’s stunning”. It’s true that nowadays the breathtaking bit often comes from the staggering panoply of techniques that have been thrown at a problem and the vast amounts of data presented.

But once in a while a “Wow” moment turns up because some inquisitive soul has peered into a nook that no one has bothered looking at before and found something amazing. Something of which almost everyone in the field would have said “Nah! Forget it! Can’t happen!! You’re wasting your time!!!”

We talked about a recent example back in March: the finding that bugs prefer to infect cancer cells rather than their normal bretheren (remarkable in itself) and that, when they do so, they can help tumours to spread — i.e. metastasize (Mapping the bug army).

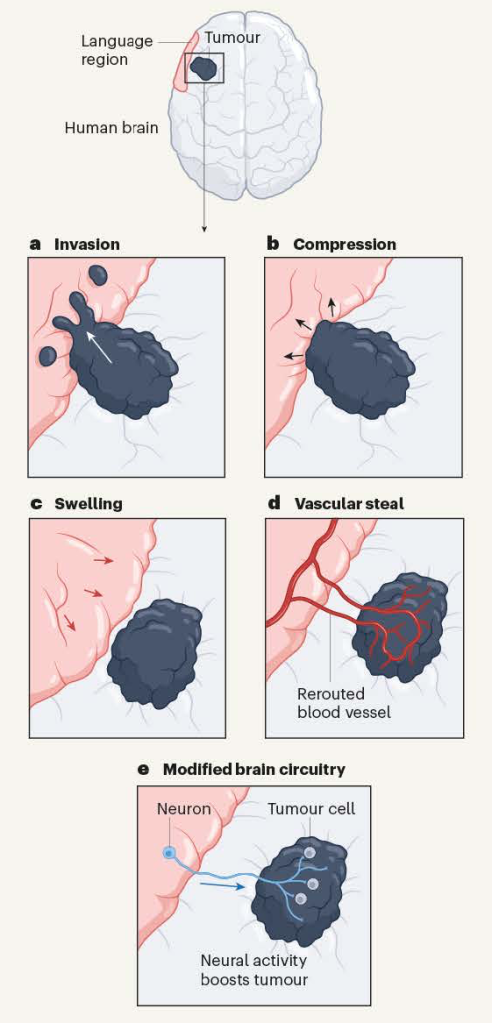

Now comes an even more startling and unpredicted finding and it’s about a type of primary brain tumour — malignant gliomas. One of the most common categories of primary brain tumour, glioma is an umbrella term for cancers of the glial cells that surround nerve endings in the brain. Glioblastoma is a type of glioma. Treatment is by surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy but the 5-year survival rate remains at around 5% and its progression is usually accompanied by progressive cognitive decline. How tumours disrupt brain function is not understood but possible mechanisms are summarised below (a-d). Broadly speaking these are the rather obvious ones of tumours invading or compressing tissues or recruiting blood supplies form the host.

Ways in which brain tumours might affect brain activity. These include (a) invasion, (b) compression, (c) swelling and (d) recruiting a blood supply (‘vascular steal’). The recent evidence from Krishna et al. reveals that tumours can form connections (synapses) with neurons. When the neurons are active (e.g., engaged in a language task) tumour growth is boosted. From Ibrahim and Taylor 2023.

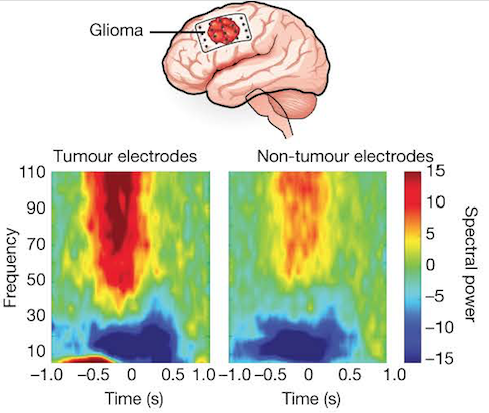

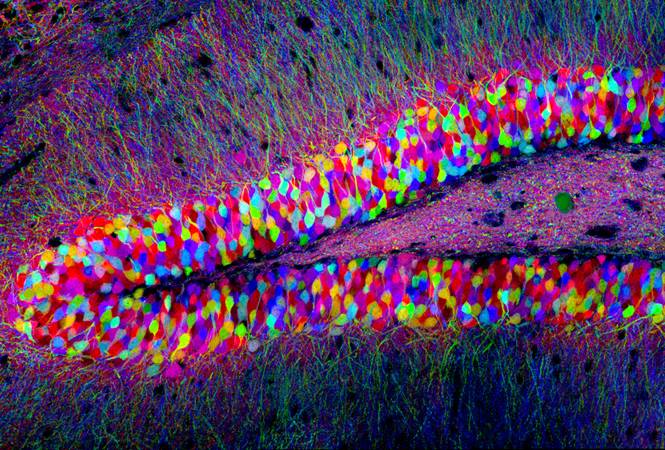

High-grade gliomas remodel long-range functional neural circuits. Top: Scheme showing a dominant hemisphere glioblastoma (i.e. a tumour in the left hemisphere — the one that controls the dominant right hand). Lower panels: Electrocorticography (a type of electrophysiological monitoring that uses electrodes placed directly on the exposed surface of the brain to record electrical activity from the cerebral cortex). The spectral data show clear separation of frequencies across tumour and non-tumour electrodes. From Krishna et al., 2023.

Some thought!

The electrical activity shown in the above figure was recorded in individuals undergoing brain surgery who were asked to name items in pictures whilst their brain-surface activity was recorded. The data show that activity in regions of the brain involved in a language task also drove activity in tumour-associated regions that do not normally function in language processing. High functional connectivity associated with neuronal signalling in tumours predicts aggressive tumour behaviour, cognitive decline and poor survival.

Unsurprisingly, functional connectivity varied across tumours and regions were classified as having high or low functional connectivity (HFC or LFC). HFC regions had raised levels of thrombospondin 1, an adhesive glycoprotein that mediates cell-to-cell and cell-to-matrix interactions — it’s involved in synapse formation and is normally secreted by astrocytes.

Moreover, addition of thrombospondin 1 to LFC regions of gliomas co-cultured with neurons induced behaviour resembling that of co-cultures with cells from the HFC region of the tumour. Conversely, when the TSP-1 inhibitor gabapentin was added to the co-cultures, glioma proliferation was reduced. Furthermore, glioma-infiltrated brain tissue enriched in TSP-1 formed synapses when grafted into the hippocampal region of the mouse brain in vivo.

Astounding!

It’s been known for a while that working synapses can link neurons to gliomas. The latest, extraordinary work from Saritha Krishna and colleagues in San Francisco has shown that conscious thought, as manifested by speech, can actually promote tumour growth. Astonishingly, high-grade gliomas functionally remodel neural circuits in the human brain, which both promotes tumour progression and impairs cognition. Not only a staggering thought but also food for thought in that the thrombospondin data clearly point the way to desperately needed new therapeutic approaches for these cancers.

References

Ibrahim GM, Taylor MD. How thought itself can drive tumour growth. Nature. 2023 May;617(7961):469-471. doi: 10.1038/d41586-023-01387-1. PMID: 37138055.

Krishna, S., Choudhury, A., Keough, M.B. et al. Glioblastoma remodelling of human neural circuits decreases survival. Nature 617, 599–607 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06036-1